This article first appeared in Prototypr, Jan 2019

Innovation requires engagement in the problems of reality as well as a willingness to imagine the delights and pitfalls of possible futures.

As makers and designers, we’re not usually up against a lack of problems to solve: we’re up against limits on resources and limits to what seems possible. That’s why leveraging creativity is crucial to solving real problems and unlocking future possibility: we have to hack the limits.

This article describes why and how I’ve used speculative games, lately a zombie apocalypse one, to teach design thinking methods to groups of innovators and changemakers. I hope you can take these ideas back to your work, or that we get to play and learn together sometime soon.

WHY GAMES + DESIGN THINKING?

Design Thinking is popular and proven technique for learning tons about a problem and coming up with a testable, human-centered idea to address it. To me, one of the key benefits is that it forces us to focus on high-value facets of an issue. It also asks us to get loose, creative, and examine assumptions — and this is where I see a crossover with games.

In SuperBetter, Jane McGonigal describes the impacts of taking a “gameful†approach.

“All games…change how we respond to stress, challenge, and pain… Being gameful means bringing the same psychological strengths we naturally display when we play games — such as optimism, creativity, courage, and determination — to real-world goals.â€

The combined skills of creativity and an optimistic courage that there can be a solution lend themselves to innovative ideas — and checking those against the needs of real people means the ideas are more valid.

Speculative Fiction & Scifi in Design

In our everyday lives, it can be hard to drum up these skills at will, but adding in the element of speculative fiction is a special sauce that I have observed turn the everyday into an adventerous opportunity to see, know, and solve together.

Speculation, from the Cambridge dictionary, is

“the activity of guessing possible answers to a question without having enough information to be certain.â€

As designers we’re often trying not to speculate, but rather to problem-solve from the most informed position available. That said, there is no omnipotent positioning. When we’re working in innovation to create new ideas and solutions, sometimes we first need to create freedom and imagination to diverge ideas which later can be run back through the grist mill of reality.

Speculative fiction is a subset of science fiction “in which the setting is other than the real world, involving supernatural, futuristic, or other imagined elements†[cite] where the authors have created worlds in parallel to the one we know by imagining answers to questions like how the world would be if there were killer desert worms, evil AI, no water, evil-er AI, or an end to the rule of law. Think Dune, The Matrix, Tank Girl, Neuromancer, The Parable of the Sower. It doesn’t have to be dystopic, though that makes for good drama — Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Looking Backward: 2000–1887 imagines utopic answers to the problem then known as industrialization.

For designers Dunne and Raby, the parents of speculative techniques, “Speculative design, by not being bound to commercial logic, opens new opportunities for designers to investigate and experiment.†[cite] Letting go of logical, normalized limits is key. Speculation is hugely powerful as a design method because we can use it to remove constraints or add elements to reality that would not otherwise exist: we create fiction by naming changes to reality — but because we start with some familiarity with reality, we still know enough about how most things work to explore.

This is a lot like real life, where there is constant change and we use our mental models to adapt, innovate, and seek opportunities in the newness. Except in a game, changes are defined and participation is optional.

Who’s In the Game?

It’s the combination of familiarity and gamefulness that makes a speculative technique work — and many companies and product creators use it, too.

SAP recently launched a book, “Science Fiction as a Starship for Enterprise Innovation,†stating“Science fiction thinking enables us to boldly reimagine our world without limiting ourselves with the constraints of yesterday’s technologies.†Amazon has been putting out speculative Future Press Releases as an innovation technique for years. PWC suggests Design Fiction as a technique that allows “extrapolating today’s sociological or economic trends and imagining a future for tomorrow, businesses [to] examine potential uses.â€

Scifi can also be used to teach and learn. In the blockchain spaces where I work currently, EOS put out a training for blockchain developers using a sci-fi/fantasy narrative. Hellhound designed an in-person Escape Game where participants embody cryptographic choices (and validate their cryptography library app).

CASE STUDIES: Two Instances of the Game

I recently designed two design thinking educational trainings as speculative games, each of which was wildly fun. Since trainings and education are too often NOT fun, I’m sharing out the process and method I used. In each of these, I worked with a co-designer and co-facilitator.

CASE STUDY 1: Zombie Apocalypse to teach Design Thinking to a team of ~12 people

I was invited to train one of the ConsenSys offices on design thinking (DT) methods, and we wanted to include a high-energy activity to reinforce the day’s learning modules and get people to quickly test using DT in a way that would be less high-stakes than their everyday work.

The participants were a group of colleagues on multiple siloed teams. I gathered insights using a simple intake form a week ahead of time, and contextual inquiry interviews once onsite. I observed that the teams had a few key problem patterns, and would be focused on their everyday work issues. I wanted to make the after-lunch hour lively, and my colleague, designer Mustafa Mufti, came up with the idea of a game. Aha! We came up with the Zombie scenario.

After a 2.5 hour morning session learning about use cases and steps of a design thinking process, we had lunch and then brought the group back together with the game.

After reassembling, we stated “There’s been an announcement: a zombie sickness has broken out overseas and we expect it’ll take three weeks to get here. You have all the resources of this office, and your challenge is to explore how might we create a vehicle for our office to survive a zombie apocalypse.â€

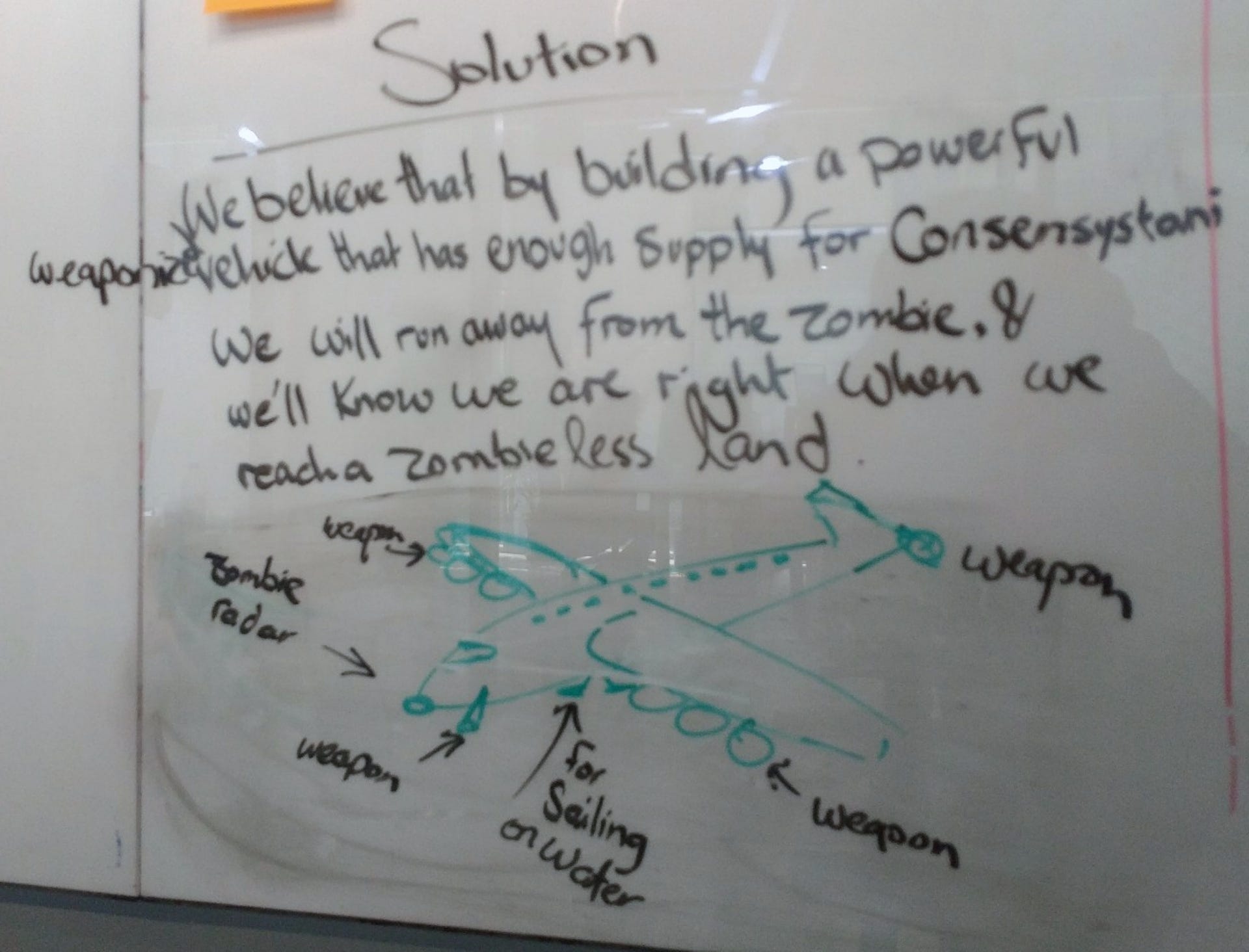

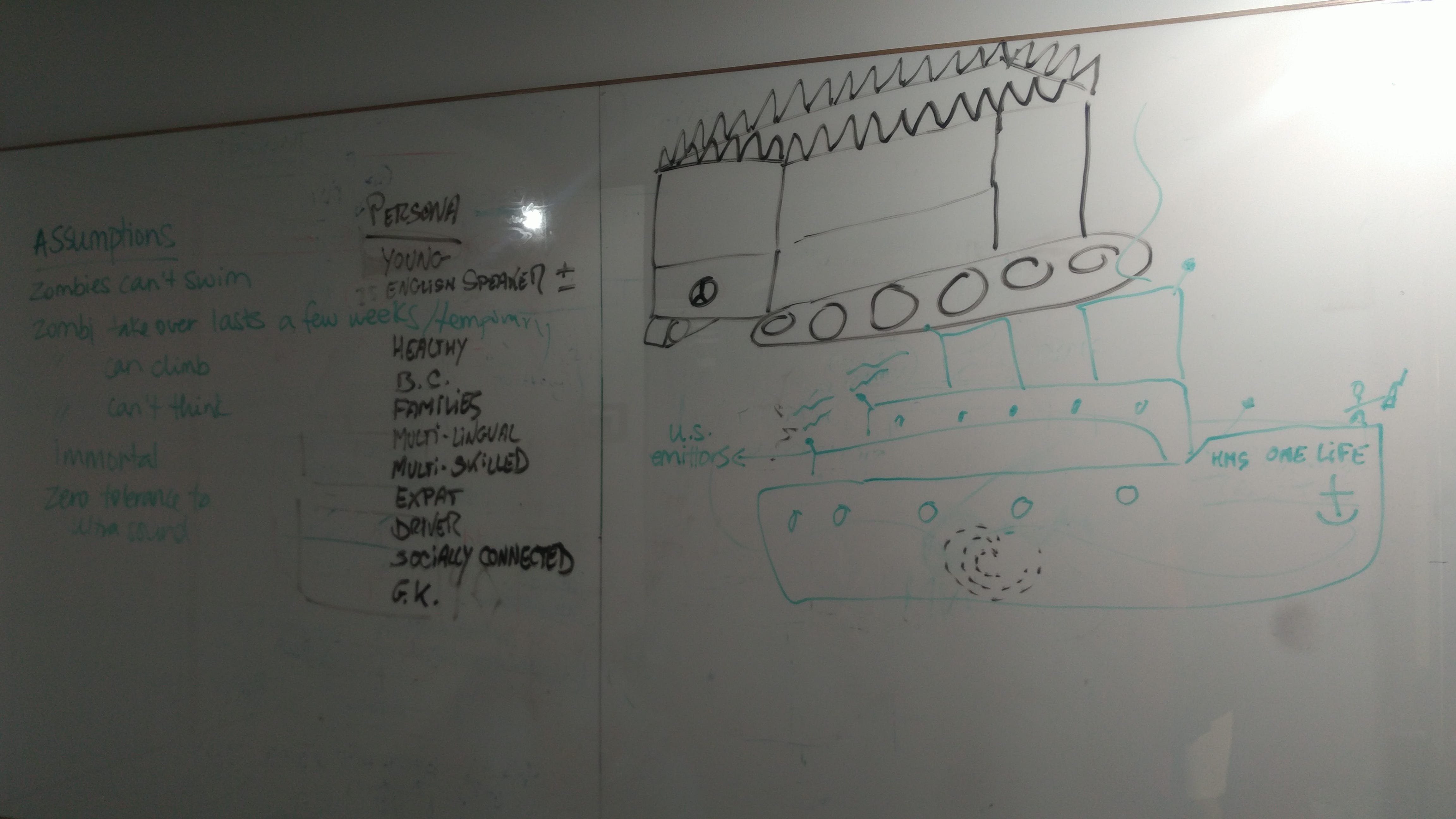

The group first needed to know that yes, everyone’s families could “count†as included in those we were solving for (and also get saved)! Then we broke people into four groups of five and they got 45 minutes to zoom through the game play: to generate empathy for a user via a persona, create a hypothesis POV or needs statement, come up with a few solution ideas, and to draw a prototype of their solution.

As the teams worked, the energy and laughter in the room indicated that we’d made a good choice — but would they use the time to learn methods?

To wrap up, we took 15 minutes to gallery walk the solutions, and asked each team to explain them *in terms of the user and hypothesis they were operating from*. Three of the four teams created boats:

The descriptions indicated that the game had gotten them to run a lightning design thinking cycle — without necessarily internalizing why the particular steps were important.

Design Takeaways:

- Time-boxing and clear instructions help people

- When people are stuck by their real problems, a game to model solving the problems will get them to be unstuck, though that doesn’t guarantee transference back to the original issues at hand

- I wished I had run the game earlier in the session, since having 30 minutes to debrief it and create an exit 30/60/90 plan was a tight fit

- People learned about DT in-game as much as in our morning exercises, so next time I resolved to go much more quickly into the game.

Which leads to how I ended up designing …

CASE STUDY 2: Zombie Apocalypse to overview Design Thinking for a Meetup of ~130 people

A few months later I was invited to be part of a Onward Labs + Chainhaus Meetup on human-centered design in blockchain applications — and the organizers wanted a twist. Rather than a panel, would I lead the meetup in a workshop? Oh, and there were usually around 130 attendees. Epic!

I immediately thought of the Zombie game — and, knowing that this would be better and more fun with a partner in action, I pinged my colleague Kandis O’Brien, of The SIX to co-facilitate. With her on board we went ahead designing a 50-minute teaching game for the event at the expansive SAP office in Manhattan.

After my first experience, I wanted to try to teach people even more experientally, so we gave a seven-minute slide presentation and then jumped into the rules of the game. Because we were gathered with a large group of blockchain enthusiasts, we gave a few extra directions and constraints with our prompts:

- We had them decide on which type of survivor… I mean user, they’d like to work on and move to a pre-set up corner of the room associated with that user. The users we identified were: Regular Folk, Ad-hoc Leaders, Formal Leaders, Zombies

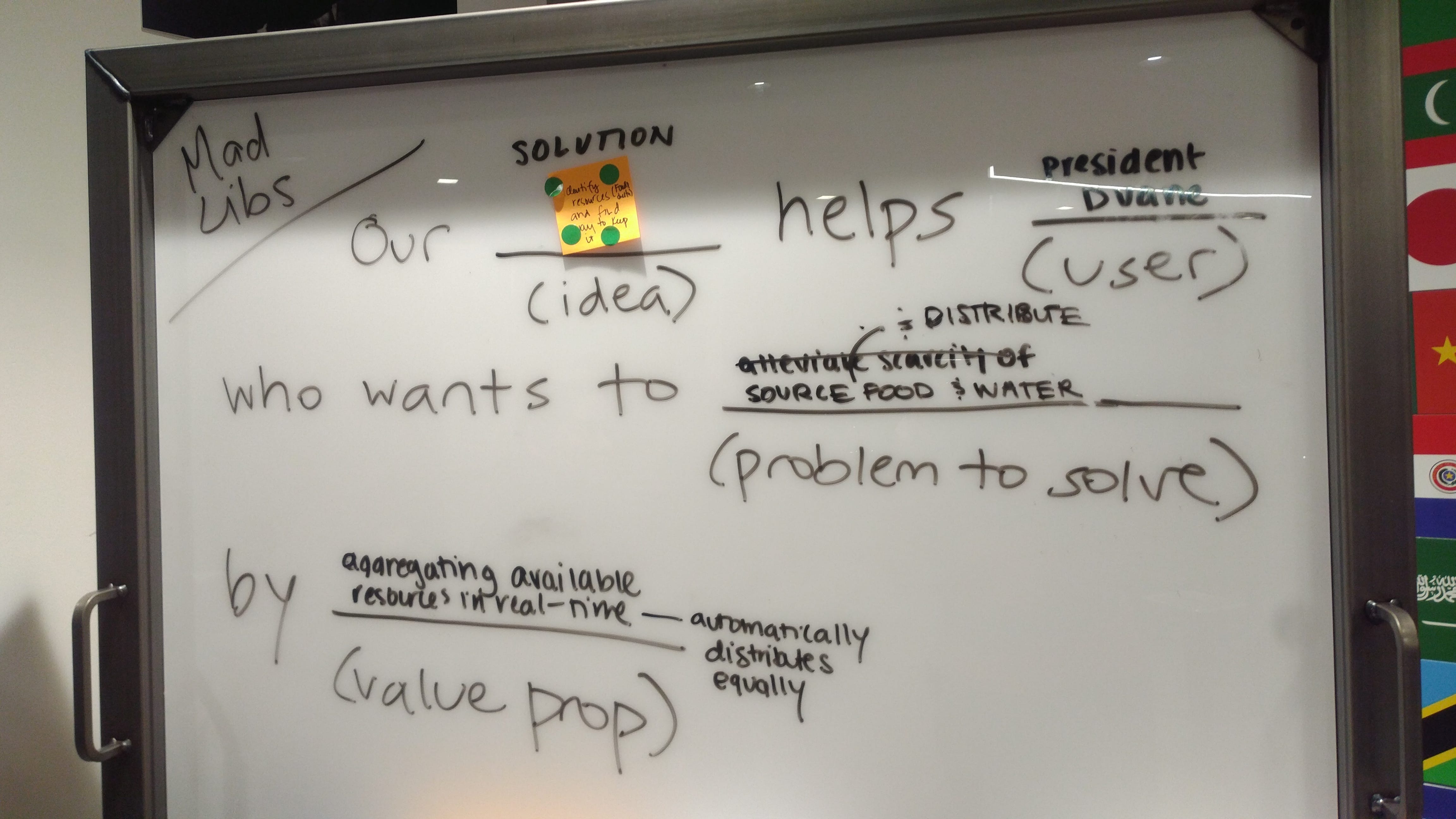

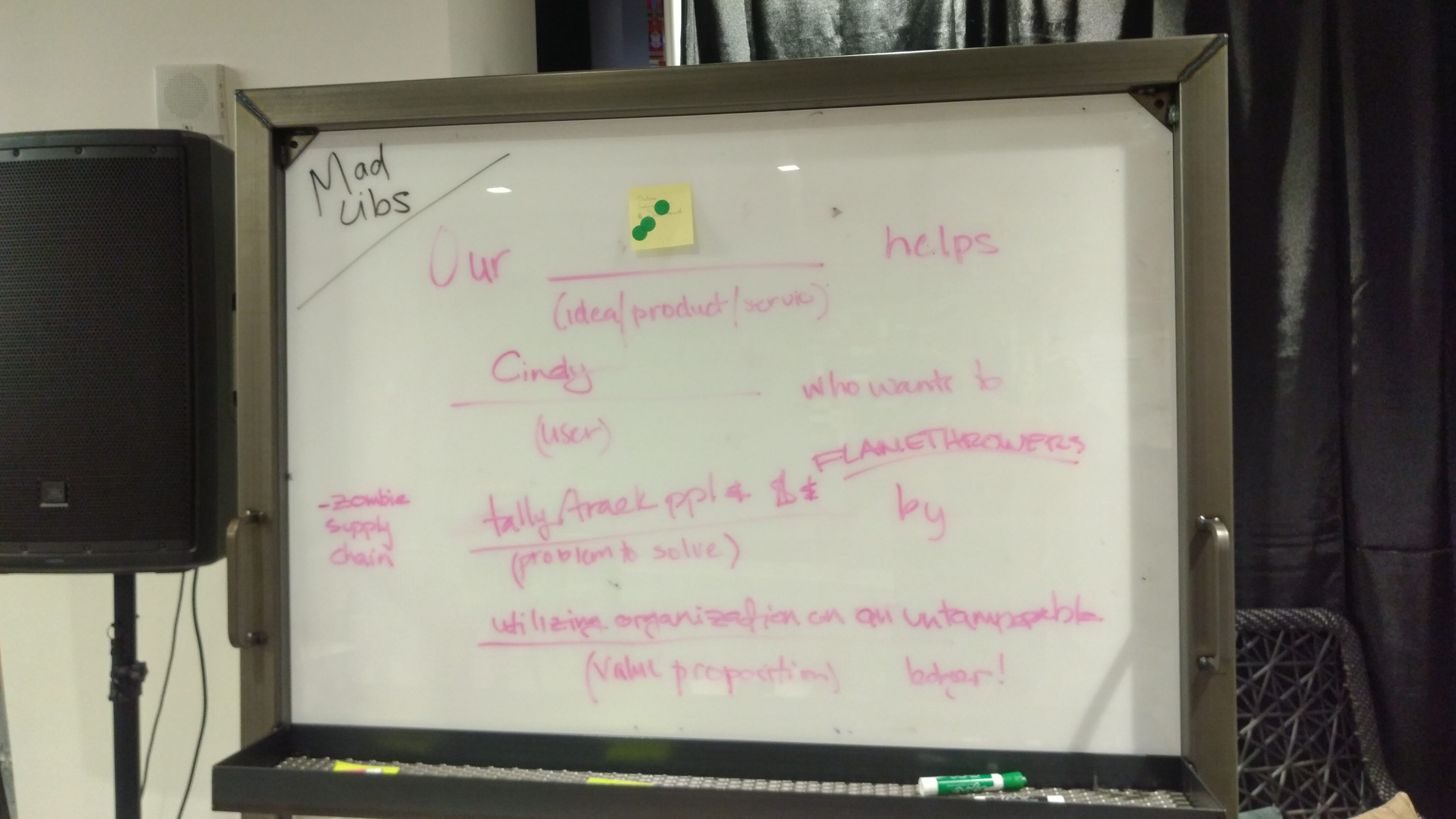

- We had them rapidly through three specific design thinking exercises:

- A Value proposition canvas

- A Pains/Gains/Jobs to be Done canvas (focusing on pain & pain relievers only — it’s a zombie apocalypse after all and we had limited time!)

- A Hypothesis statement madlib

Then we discussed the ideas in terms of Desirability, Viability, and Feasibility, to lead into the panel that was focused on the latter of these two traits/

Here’s a few of the outcomes:

Once we got going, the experience for me was a blend of emceeing, facilitating, and immersive theatre crowd control — the groups really got into solving the problems of their assigned users and came up with some thoughtful ideas that I observed deep conversations about.

Design Takeaways:

- I would absolutely run this again, and definitely with a co-facilitator given the number of people. I would try to squeeze another 10–15 minutes (or hey, another hour) but 50–60 minutes is enough time to explain, play, and debrief if you facilitate it fiercely.

- The gamification aspects of creativity and courageous problem-solving really stood out in this instance, I think because we told people it was a game. We wanted to design a high-energy, post-work engagement that was pedagogically meaningful but knew better than to describe it to an audience that way.

Why Zombies work

While I don’t have any research here, one thing I observed when working with the first team stands out to me as an insight into why zombies are a useful trope (besides the fact it’s fun to invoke a currently familiar meme).

Several teams in the office brought up that they didn’t know much, if anything, about the zombies. How would they behave? Can they swim? Will they avoid boats?

Hmmm, I got to say, wouldn’t it be helpful to be able to research them? What do you do otherwise when you need research but don’t have it?

As human-centered designers we’re constantly advocating for our users brains to be eaten, I mean needs to be centered. Zombies are a metaphor that allows us to highlight the need to empathize, and the things we might miss when we don’t.

Speculative Design Techniques

Seeing people lean into creating the fiction narratives of the two games I ran was delightful; imagination is a muscle and we can work it in fun ways to prepare us to use it for consequential purposes.

When we’re designing the future, scifi and speculative methods can help us create without any roadmap. Here’s three ways to use imaginative speculation in innovation design, drawn from the games I created:

- Success is certain: Imagine its X years from now and things have gone “well†— what does that mean? What had to happen now so that you’ll know the thing you were working on went well? *This helps us imagine results, which we can reverse-engineer actions from — think Future Press Release.*

- Constraints are gone: Imagine you have a million (or billion) dollars to address this issue — what will you do? *This helps us ideate without knee-jerk blockers to our ideas — think Edward Bellamy or Microsoft.

- You’re in an unreal situation: So, today the UN announced that aliens are real — How might you use XYZ skill, given this information? *This helps us apply something in a no-stakes context. It’s not reality, so it’s ok to try things on! Think: …Zombie Apocalypse!

Where next?

There’s plenty of times when it’s not possible or right to give people the “real†problems to engage with; instead, you can give them games to practice and learn from.

If you’re working in blockchain, check out Andrea Morales-Coto’s Participatory Design for Cryptoeconomic Systems; in particular she goes into methods and formats and made a tarot card deck you can use! If you are interested in social impact and speculation, Octavia’s Brood by adrienne maree brown is an excellent scifi exploration anthology. Finally, check out Speculative Everything by the infamous speculative designers Dunne and Raby.

As changemakers, facilitators, and teachers, the ability to engage participants and encourage creative thinking is nontrivial. The problems we hope to solve together are, similarly, massive and sticky. Don’t they deserve the best, most energetic, most aha-moment laden contexts we can give them?

So, have you ever used a speculative teaching method? Tried to create a memorable experience to drive a point home? Gamified as an engagement tactic? Tell me about it below!

****

Hadassah Damien is a design thinking facilitator working at the intersection of innovations in technology and participatory experiences, as well as an artist and economics researcher.