What We’re Looking For

The first place I began researching was in and around the concepts of “activist art†and “political art,†both of which are colloquial terms that I hear and use regularly.  I was hoping to find a repository where an understanding of the critical importance of the role of those using or participating in a cultural form with political intent.

One of the very strange situations I encountered – which has made me push harder in my research – is that I started out not knowing what to call what I wanted to study. Part of the point of higher education is this search for specificity, to really pin down what something is using language. Whether this urge is a phallocentric domination-culture act of naming-as-a-form-of-control or not; All I know is that when I’ve put “political art†and “activist art†into various academic search engines and article databases, the taxonomy of the academy keeps directing me to the recently-named phenomena known as socially engaged, participatory art.

So, what is that?

Participatory art is a set of practices centered around creating experiences that are about the relationship[s] to ones self via other people, rather than about one’s relationship to one’s self via stuff you’re looking at.

This is defined by Suzana Milevska as implementing a “shift from establishing relations between objects towards establishing relations between subjects…influenced by philosophical or sociological theories; and today is mainly appropriated by post-conceptual, socially and politically engaged art, or by art activism.†And, in Mary Jane Jacob’s words, there has been a “shift the role of the viewer from passive spectator to active art-maker.â€

Before the high-art participatory turn of the 1990’s, art that involved subjects as the point of the piece included, according to Milevska, “the video art practice of the independent and guerrilla TV stations (e.g. Top Value TV), participatory theatres such as The Living Theatre, or the early happenings by Alan Kaprow and Mike Kelly from the 60s, as well as the »new genre public art« coined by Suzanne Lacy.â€

These are art practices that involve people are more than “just†spectators, informed by ideas around spectacle society; social empowerment, and the placement of art in everyday life rather than galleries.

The idea is that participants are not just following artists’ instructions, rather “Participation is the activation of certain relations that is initiated and directed by the artists and often encouraged by art institutions, and that sometimes becomes the sole goal of certain art projects.â€

How does it work as art? And what are some problems with this? There is a differentiation between participatory, interactive, and involved art, where the higher the participation-level the “better†the art is, or the more involved participants are, the more authentic –and complicated— their experiences and therefore, the more effective the art piece is.

Critiques include concerns that “this is not art†and “this is exploiting people.†The first concern is frankly annoyingly bourgoise, as it requires either an expert to oversee the creation of the art, or a deep critical analysis of framing and art works that the users/participants of the art are distanced from. The latter question merits more analysis, since the point of participatory art is, at a base level, some kind of experientality–whether that experience leads to consciousness, social change, newly connected groups or interactions, or revolutionary activity—the most basic hope is that this experience is non-exploitative. This is extra important, in light of the fact that much participatory art is intended to include folks from already-marginalized social groups [poor folks, elders, people of color, displaced folks, lgbtq folks, et al].

Wait?! What happened to “activist art�

Great question! In studying Art, the ways of talking about it have a tendency to remain attached to critical theory and philosophy. Part of this shift to using esoteric humanities disciplines to name art that involves publics in important ways “participatory†is, I believe, a way for this work to be professionalized and made fundable and palatable by institutions. There is, however, both a strong history as well as current representations of “activist art†which differ from participatory art in a few ways.

In a catalog essay for a 1984 exhibition entitled Art & Ideology, the critic and activist, Lucy R. Lippard, described activist art as a practice whereby: “…some element of the art takes place in the “outside world,†including some teaching and media practice as well as community and labor organizing, public political work, and organizing within artist’s community,†quotes Gregory Sholette.

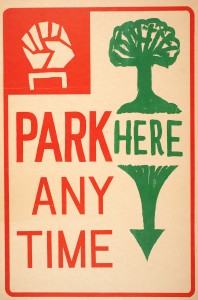

V.S. Reed, in his book The Art of Protest, describes activist arts as those cultural forms that which emerge from social movements, which are intended to create or support social change. A cultural form can also be called a text, but what is meant is any production [a book, a poster, a song, a street puppet performance, etc.] that is made from a social basis.

What is NOT participatory art that might still be activist art? Well, a few examples include photocopy and mail art; punk DIY/skillshare culture and shows; the powerful collective, creative protests that emerged out of AIDS activism [ACT-UP, Gran Fury]; 1980s collaboration culture that produced Women’s Art/Activist Coalition [WAC] and Political Art Documentation/Distribution [PAD/D]; The Reverend Billy’s choir might utilize involvement but not participation … It appears that art history has its own understandings of the role of participants within this participatory turn in art, and activist cultures have another.

Questions:

- Is all activist art participatory? Is all participatory art activist?

- What is it about art that is created by the participation of viewer/makers, rather than “merely†witnessed by viewers, that is important or part of this shift?

- And why are folks so interested in the fact that art has a “shift†anyway?

- Why are activists and artists unable to share theoretical or disciplinary language?

Suggested Readings:

- “Participatory Art: A Paradigm Shift from Objects to Subjects,†Suzana Milevska

http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=1761&lang=en - “News From Nowhere: Activist Art and After, A Report from New York City.†Gregory Scholette. In 31 Readings on Art, Activism & Participation [in the month of January]: An Art & Activism Reader, 2007. Originally published in Third Text #45, Winter 1999, 45-56. http://thinktank.boxwith.com/docs/reader/art-activism-reader.pdf

- The art of protest: Culture and activism from the civil rights movement to the streets of Seattle, T.V. Reed, 2005. http://www.scribd.com/doc/29444402/Reed-The-Art-of-Protest-Minnesota-2005